Isaiah Villars, my great-great-grandfather on my dad's side, shared his diaries and memories with his son Ulysses, who transcribed everything in a massive handwritten journal dated 1906. This excerpt is from that journal, which Ulysses wrote in third person.

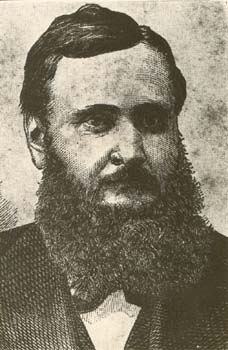

Reverend Isaiah Villars

Isaiah Villars of

Vernontown, Clinton County, Ohio, and Miss Mary Helen Thompson of Catlin,

Vermillion County, Illinois, were joined in holy matrimony , Rev. George W.

Pate officiating, on October 5, 1858.

A wedding tour was determined on, and it

was made in the two-horse waggon and by the same team, 350 miles to the Ohio

home of the groom and 350 miles back again to their Illinois home two miles

south of the village of Catlin.

Winter was soon on. It was given to making

posts and slats for the first field. The first table off which they ate the

first meal was a broad board that rested on their knees while their chairs were

two wooden boxes. Their first outfit was quite limited. The family altar was

erected before they closed their eyes the first night for sleep, and it was

never permitted to go down.

Miss Thompson, though young, had taught

the district school of her native neighborhood. Her father’s name was John; he was of stirling Scotch descent. Her

mother’s maiden name was Esther Payne. Father Payne lived to a great age, and

the daughter Esther died in her ninety-third year. The Payne family was large

and identified with the early history of Danville, Illinois.

There were born to John and Esther

Thompson, Lewis M., Malissa, Martha A., Silvester, Mary Helen, Harriet, and

John Thompson. John, the youngest, died when nineteen years of age. All the

others married and reared families of worthy and highly esteemed sons and

daughters, none of whom brought any reproach upon the family name.

John Thompson died September 12, 1861,

aged 65 years, 4 months and 22 days. Esther Payne Thompson died June 21st,

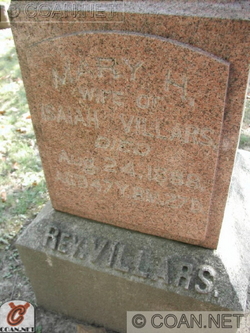

1899, aged 92 years, 3 months and 9 days. Mary Helen Villars, wife of Rev. I.

Villars, died August 24th, 1888, aged 47 years, 8 months, and 27 days. An

account of it appears elsewhere.

After making their home on the open

prairie, in due time their first born came. His name was Rosswell Chase, the

first for a very special friend of the Thompson family and the second for Hon.

Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, the ideal statesman of the young father Villars. (The

making of the farm is the old story of labor.)

The war for the union came on. Both

husband and wife were patriotic, and it was concluded that sufficient provider

(provender?) had been accumulated to keep mother and child. A cavalry company

had been partly enlisted at Catlin, sufficient to venture on electing officers.

In his absence Isaiah was elected Orderly Sergeant, and mounting “Old Tom”, his

favorite horse, went to Catlin to assist in completing the organization, when,

lo, most of the already enrolled showed the “white feather” and backed out

before they had smelt powder. Company D of the 35th Illinois Volunteer Infantry

in camp at Catlin, was to go to the Capital (Springfield) next morning and

report to the Governor for service.

Isaiah put spurs to his horse and rode in

haste home and said to his wife that if he went at all he must go with the

Infantry next morning. They talked it over and the result was his enlistment on

the train after the train was on the way.

He always felt that while the

father-in-law Thompson was ardently patriotic, the blow of Isaiah’s enlistment

was great, and when taken with a serious sickness, the thought of the

loneliness of his daughter Mary in a community not too friendly to loyal

people, proved too much for his failing health, and Mr. Thompson passed away in

September of 1861.

On the forced march (under Gen. John C.

Freemont) of Springfield, Missouri to drive General Price of the Confederacy

from that part of the state, Comrade Villars was taken with the bloody flux, a

fearful disease having many victims among the exposed and weary soldiers. Then

he knew real homesickness. He wrote to his wife, if possible, to come to him.

His bed was the bare floor of a deserted house. He was alone in a small room,.

Under him was but a simple blanket, and a handful of coarse buckwheat straw --

not a bundle, but what one hand could hold -- placed under the hipbone so as to

prevent it wearing through the skin.

His fever increased rapidly , and in

forty-eight hours delirium set in. In his dreams he thought of the letter he

had written, and that his good wife had made the venture for his side, the

nearest point to Springfield, by rail, being 125 miles over mountains, hills

and valleys. She had arrived, in his dream, and took the tenderest care of him,

cooling his brow, and allaying the fever until he would “come to himself”

refreshed, and then just as he would open his eyes to see her, she would pass

out of the door and he would just see the skirt of her dress as the door closed

after her. Then he would cry to know what she meant, and ask why she would not

remain till he could speak to her. It was all a dream, delirium.

But after a week, the fever was broken and

the patient was himself again. But he was an infant in weakness. Orders came to

take all the sick to Beulah, Missouri, 125 miles away, that they could be sent

by rail to St. Louis. He was placed in a stagecoach with a delirious soldier of

the same regiment, who died that night and was buried next morning. His name

was Isaiah Pillars of Company 1. This excitement he could not stand, both

compelled to sit erect, and cried to be put in a two-horse farm waggon (sic) of

a refugee, on its bare floor, and that was his conveyance until the railroad

was reached.

A new distress came to him. He remembered

he had written to his wife to come, but fortunately the authorities did not

send it. But he knew it not, and now he is about to be removed and while he is

to be taken one route to the railroad, his wife will be coming another, and

through an enemy’s country with “bushwhackers” everywhere, and what could a

woman do in such a country. The painful anxiety was beyond description, but

need not have been, had he but known that the letter had never been sent.

From one to three graves were filled every

night. George Worley, a family friend some miles north of the Thompson

homestead, had received a letter giving an account of this caravan of the sick,

and a list of the names of the dead and buried. Isaiah Villars was among the

number. The wife was at her father’s house when word came. A messenger was sent

to see the letter. It confirmed the report.

In getting things ready to secure if

possible the removal of the body home, she found in the post office at Catlin a

letter in her husband’s own hand, not knowing but it was his last message on

earth. But on opening it, found that he had survived the trip, was then in

Chesnut Street Hospital, St. Louis, and if she could send him just a little

money he would get a furlough and come home. It was soon forthcoming and nearer

dead than alive, on a midnight train at Catlin, a neighbor by name of Olmstead

took him on horseback the two mile ride home, fearing to stop short of it lest

he should die.

He rallied quickly but not completely.

During the thirty days alloted him, his darling boy, the picture of health and

flesh, took lung fever and in spite of all, after ten days passed away. He died

March 9th, 1862. Two days afterward, he was taken across the fields, the roads

being impassible, two wagons holding coffin and procession, to a little grave

in the “Butler’s Burying Ground” just outside of Catlin, west, on the south

side of the Wabash railroad.

A soldier’s metal (sic, s/b "mettle")

was tried by the side of the newmade grave. One day more and the furlough

expires. It was a trial to say the first “goodby” but when, with scalding

tears, he must say this second goodby at the newmade grave of their firstborn,

just there the fountain was broken up and a torrent of sorrow simply drowned

all utterances.

He returned to St. Louis, thence to

Beulah, and in the early spring marched to Forsyth, Arkansas on White River. Here

he came near losing his life by drowning.

- Isaiah Villars survived the war and lived to a ripe old age. He only had one other child - Ulysses, who transcribed this.

- Isaiah (he pronounced it "Eye-SIGH-ah") was a Methodist minister for 48 years; also a soldier, author, college president, chaplain at the Illinois State Penitentiary at Joliet, and pioneer.

- An obituary notes that he was: “Born on a farm, converted at the age of sixteen, pupil in the public schools, student at a Quaker college, married in 1858, corporal in Company D, 35th Illinois Infantry (almost four years in the Civil War), a minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church for practically 50 years, president of McKendree College, chaplain in the Grand Army of Illinois, chaplain of the state penitentiary at Joliet, author of several books, constant contributor to the press, one of the organizers of the Prohibition Party, temperance lecturer, Doctor of Divinity by grave of DePauw University.”

How wonderful that you have this. I spent part of yesterday googling Civil War pictures--it's very hard to imagine life back then and to imagine those men and boys going to war in open fields...well. It is a stark reminder of how far this country has come and to whom we owe our roots.

ReplyDeleteMaria - I always thought of the Civil War as something very distant until I got into genealogy. Another ancestor of mine was killed at Shiloh (the battle of the Hornet's Nest) and I actually found a mention of his death in a history book. Now I'm fascinated with it!

ReplyDeleteIt's just so striking and sad thinking of all those young men marching into war--little protection against the elements or the war, just valor and dreams. I saw the battlefields with the bodies on it and thought, "Someone was the front line. They marched out there shooting right in the front line of that field." And you gotta wonder than anyone ever walked away. And you gotta wonder than anyone would be in that front line because how could you expect to walk away!!!

ReplyDeletePictures from that era have always struck me because of how little people had. Your description of the wedding couple eating on a board and the boxes to sit on--that sort of thing. I have more clothes in my closet now than most of them owned in a lifetime! Some of the pictures from the battlefield showed men without shoes and/or such battered clothing overall even when they were posing before a battle. It's just incredible to consider the conditions.

Isaiah's journals has a few descriptions of the hardships he endured during the war. My great-great grandfather on my mom's side also survived the war, but suffered throughout the rest of his life from a weakness in his lungs that developed from the awful conditions he survived. It's hard to conceive how many miles they walked, often without shoes.

ReplyDelete